Some days ago I was joking with a friend of making t-shirts with a “Open Data is my mission” slogan. The problem of that mission is that its object is not particularly well defined.

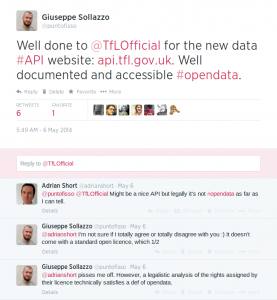

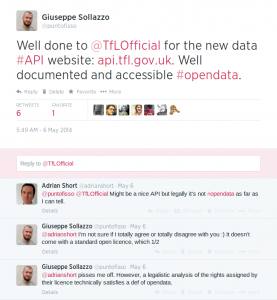

I was involved in a couple of interesting discussions via Twitter about this, with a couple of people whose opinion I really value. On the day TfL announced their new api.tfl.gov.uk I tweeted my happiness about their Open Data licence. My happiness was not shared by Adrian Short:

Adrian suggested their API was all but an open one; that as it had restrictions, especially the requirement to register for a key, it could not be linked to the adjective “Open”. (The whole conversation can be accessed here).

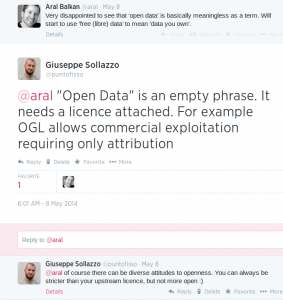

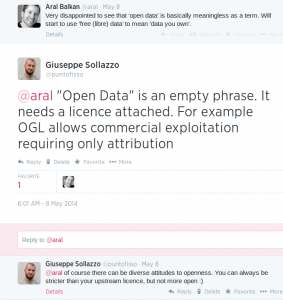

In a similar direction went a quick exchange with Aral Balkan:

These two conversations highlight a curious problem in the “Open” communities, whether they are -Source, -Data, -Whatever: we’re talking about some very loosely defined concepts. As I say in my response to Aral: Open Data is just a phrase – what really matters is the licence attached to the data.

Openness is measured on a continuous scale. If there is a threshold below which we shouldn’t call some data “open”, that threshold has not been defined yet. It’s relative (to the data, to the context, to the country, to the user), it’s flexible, it’s got several possible meanings.

My personal position is to call open data whatever comes with no use restrictions (i.e.: you can use the data for whatever purpose you like). In legal terms, however, this gets complicated because we need to assign a licence to the data. When working with ODUG, for example, I always make a point of not accepting data releases with anything less than an Open Government Licence (or its Creative Commons / Open Database Licence equivalents).

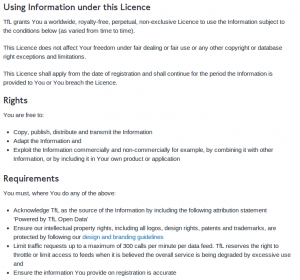

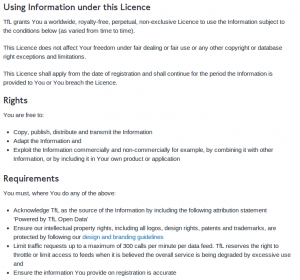

Furthermore, in the not-so-public sector (which is what I generally call TfL), things are clearly complex, especially given the expectation (which I do not personally agree with, but this has no effect to this discussion) that a transport agency in a metropolis should be profit-making. TfL’s licence is probably not the best worded ever, but it is an Open Licence:

Yes, as Adrian notes, TfL can revise the Licence at any point. But until they do, they allow to copy, adapt, exploit the information with only requirement that of attribution. This is not much different from OGL.

Does the requirement to sign up for an API key justify the critique? This is clearly a complication that comes from the real-time nature of this data. A system with such a huge amount of data generated in a short time needs provisioning, and the best provisioning comes from knowing how many users can access the system. In this case I don’t think that having to register for a key is affecting the openness of the data because there is no restriction on who can register. Of course an improvement would be to have the possibility of anonymous registrations and I would support this; however, the SLA might still give priority to users who are not anonymous, simply because it knows more about their requirements. Openness is a compromise, one that comes from opposing needs clashing.

The non-real time datasets could be distributed without registration, this is where I agree with Adrian, but I don’t think this can justify the negativity against this data release, a step that goes in the right direction. Does anyone want to bring this up with TfL?

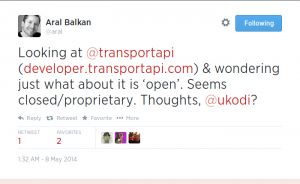

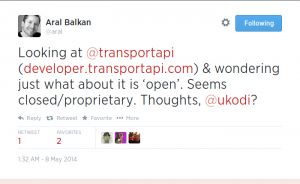

On a similar note, Aral initiated a somewhat long and inflamed thread about a similar issue: the use of Open Data and the expectation that from something open should descend something open. In this case the focus was on my friends at @transportapi, whom I think are doing a great job of showing how Open Data can create business.

(Full conversation here).

Some interesting questions emerge from the thread:

- Aral Balkan: “How’s this not closing off open data via a proprietary system only to license it commercially via an API?”

- Emer Coleman: “We are DaaS provider. 1,000 hits a day for free then charge per hit with SLA’s once exceeded but also don’t have any IP on downstream products or services and more open licensing”.

The thread goes on and on with similarly opposing views. The question emerging is one: is there a (moral) obligation for Open Data users to be as open as the starting data?

I will take the “risk” of being seen as an Open Data moderate: my view is that this question doesn’t have a straight answer, it all depends on the level of maturity of the Open Data movement in that specific context and the product. Once again, as in TfL’s case, we’re talking about a relevant amount of real-time data. In this specific case, the data is heavily modified by Transport API to make it cleaner. It is a relevant chunk of work. It would be unsustainable to provide it for free and without registration the service level would soon degrade. Hence, once again we need a compromise. Building sustainable businesses on top of Open Data is still something new. But sticking to the legal: the licence does not place limitations on the use of the data. This can be open enough for some and not for others. “Open Data is a broad church”, says Jonathan Raper in the same thread. Sustainable Open Data-powered businesses create a virtuous circle that encourages more data releases, and I think we should welcome it.

One final note: we should probably stop capitalising the words “open data” and accept that multiple views will always be possible. Once again, open data is a compromise, as this debate shows. By keeping it on we can make that compromise produce useful results and the openness agenda advance.