1. One of the best camps I’ve attended recently

2. I want @davebriggs’ shirt

3. “Only thing that makes you special is tax payer funding” is the most stupid thing I’ve read

4. “We are special because we’re here on a Saturday, in our own time, trying to solve the taxpayer’s problems” is the best reply I managed to give

5. So many local government officers around is a very good sign

6. So little councillors/politicians around is a not so very good sign

7. Tree macro-areas for discussion and action: Transparency, Participatory democracy, Data geekism

8. I’ve finally met Baskers!

9. In the LocalGov/PublicSector communities I know more people than I thought

10. Social Media strategy evaluation is difficult (not just in the public sector): how can you evaluate a conversation?

11. Defining the goals of that strategy is the most interesting part – and the outcome of that evaluation is not necessarily a number

12. Kudos to @LinkedGov and @danpaulsmith for an amazing service and session showing how Linked Data can become interesting and useful to everyone

13. UkGovCamp is political, but it involves people with very different ideological backgrounds

14. I’d like to see more people from the public sector taking part to this: many problems are similar, as it is resource availability

15. Wow, I can present myself to an audience with a microphone. I used to go piping red doing that!

16. Never catch flu the last day of such a great event

17. Next time: get speaker/organiser’s name on the agenda. It helps identifying it.

18. I might accept @the_anke’s offer of conversations in German, next time 😉

19. Open Data is great but we need to define what it is, how to share it, and how to get people engaged.

20. Government (GDS) involvement is a great and exciting thing, but open data (and the movement) will succeed only with citizens/developer/activists maintaining ownership of action

Author: puntofisso

Programmers

Reinventing the while since the 70s.

Sue Black’s wrote a great blog post about whether the history of computer science should be part of the GCSE Computing programme. This is a new programme offered initially by OCR as a pilot, and now as standard GCSE. It offers a qualification in three practical parts, lacking completely a more philosophical approach to Computer Science.

Although a mainly practical approach to computing might be justified at this level, a total absence of the wider issues of Computer Science is appalling. So Sue’s idea of adding the History of Computer Science to this qualification would improve not just the quality of the qualification itself, but also the understanding of the contribution of Computer Science to our society. Joining voices with Sue, I would like to highlight some simple points about why Computer Science history is important:

- from a purely technical perspective, learning how things developed leads to better skills; we require nuclear physicists to study Newton’s laws, and astronomers to have a grasp of Kepler’s ideas. Knowing the history of punched cards and batch processing on mainframes will make today’s developers deal with their work more effectively.

- Computer Science made a substantial contribution, most famously through the work of cryptoanalysts at Bletchley Park, to the Allies’ victory in World War II. Computer Science made the difference between a Europe dominated by dictatorships and a democratic one.

- The history of businesses in Computer Science is one of visions and missions, one of intense fights over the improvement of efficiency, effectiveness and commitment to users; it’s a story of genius ideas and financial mistakes; it’s a story of alternative views of how to get to the market, of giants that created giants. In short, it’s a story that every aspiring entrepreneur should learn before even trying.

- Studying the more philosophical aspects of Computer Science, the complexity and computability theories, the halting problem, the Goedel’s theorems, can give a student an amazing insight of how humans perceive reality and approach problems.

- The history of people in Computer Science is a history of science, knowledge, research, passion; it’s also a telling story about civil liberties and bigotry. Ada Lovelace, a woman, is hailed as the first programmer of history; Alan Turing, a gay man who was persecuted (not a typo for prosecuted) for what he was, is credited with developing modern computer science and leading the effort to decrypt Nazi communications. Knowing this story is a way to learn the contribution of each and every person to the development of a great science.

Studying the history of Computing as a science is part of my background. The path going through Babbage, Lady Lovelace, Turing, Goedel, and Dijkstra was possibly the most mind opening of my life. I would really like to see new generations enjoy the same mind opening experience.

I have submitted my views to the Public Data Corporation consultation. Here are the answers.

Charging

Q1 How do you think Government should best balance its objectives around increasing access to data and providing more freely available data for re-use year on year within the constraints of affordability? Please provide evidence to support your answer where possible.

I strongly believe that the Government should do its best to keep free as much as data it’s possible. In all honesty, I believe that all data should be kept free as there are two possible situations:

– data are already available, or refer to processes that already produce data, in which case the cost of publishing can be kept relatively low;

– data are not available, in which case one should ask why this dataset is required.

In the second case, I would suggest that the agency releasing such dataset could gain in efficiency, justifying the release of the data for free to the public.

There is also a consideration of what a data-based business model should look like. I think companies and individuals using public data as a basis for their business are finding it very hard to generate ongoing profit based on data only. Which brings me to the idea that charging for such data might actually make such companies lose their interest in using them, with a loss of business and service to the community.

A good example to this point is represented by real-time transport-related mobile apps: they provide, often for a price that is very low, an invaluable service to the public. These are data that are already available to some agencies, as they are generated by a process of driving the transport business to higher efficiency and effectiveness by knowing the location of the transport agents (buses, trains, etc…). Although in some cases this requires costs for servers to support a high demand, in absolute and relative terms we are talking about limited resources. Such limited resources create a great service to the public, effectiveness for the transport company, and possibly some profit for the entity releasing the software. The wider benefit of the release of these data for free is much more important than the recovery of costs through a charge. That’s why I question in first place the need for a Public Data Corporation, if its goal is just that of charging for access to data.

Q2 Are there particular datasets or information that you believe would create particular economic or social benefits if they were available free for use and re-use? Who would these benefit and how? Please provide evidence to support your answer where possible.

Surely, transport and location based datasets are the most important: they allow careful planning by the public and, as a result, a more efficient society. But I would not talk about specific datasets. I would rather suggest the Government to have an ongoing relationship with the data community: hear what developers, activists, volunteers, charities ask for, and see if such requests can be satisfied by issuing a dataset appropriately.

Q3 What do you think the impacts of the three options would be for you and/or other groups outlined above? Please provide evidence to support your answer where possible.

As I outlined in Question 1, I think data should be kept free. Hence, the best option is Option 1, provided that there is a genuine commitment to release more data for free. As I said the real question is whether data are available or not. When data are available, publishing and managing their update is a marginal cost to the initial process. When data are not available, the focus should be moved to understanding whether their publication can improve ongoing processes.

The freemium model works in the assumption that there is a big gap in the provision of a basic version of the data with respect to a more advanced service. I do not believe that this assumption holds for most of the datasets in the public domain.

Q4 A further variation of any of the options could be to encourage PDC and its constituent parts to make better use of the flexibility to develop commercial data products and services outside of their public task. What do you think the impacts of this might be?

I think that organisations involved in the PDC should keep to their public task.

The risk in letting them develop commercial data product outside the public task is that the quality of the free portion of the data would plummet.

Q5 Are there any alternative options that might balance Government’s objectives which are not covered here? Please provide details and evidence to support your response where possible.

I cannot see any other viable alternative, unless we consider the very unpopular idea of asking the developers for part of their profit, if any, in a way that shadows the mobile apps market. However, I think that the overhead in doing so is not worth setting up such a system.

Licensing

Q1 To what extent do you agree that there should be greater consistency, clarity and simplicity in the licensing regime adopted by a PDC?

I think that realistically developers and other people interested in getting access to public data want to have clear and simple terms and conditions. I am not a legal expert and cannot possibly comment on the content of such licensing regime, but I would like it to be clear, short, and understandable to people who are not lawyers. The Open Government License, and any Creative Commons derivative, is a good example.

Q2 To what extent do you think each of the options set out would address those issues (or any others)? Please provide evidence to support your comments where possible.

Once again, I would like to stress the fact that the Open Government Licence is the ideal licence for any open-data. This would suit Option 3: creating a single PDC licence agreement, with a simple, clear, short licence to cover all situations. Option 2, an overarching PDC licence agreement that groups all commonalities of a number of licence, is possibly a second best, but it comes with a great risk of lack of simplicity, and confusion.

Option 1, a use-based portfolio of standard licences, would possible make sense in terms of clarity, but it complicates greatly the management of legal issue for the licensees. The consultation highlights that “rights and associated charges [would be] tailored to specific markets”, making it very difficult to understand such licences.

Naturally, if these licences need to be more restrictive than the Open Government Licence, I still think that a single restrictive licence, on the model of what the State of Queensland in Australia has done, would be the best idea for maintaining clarity and simplicity.

Q3 What do you think the advantages and disadvantages of each of the options would be? Please provide evidence to support your comments

It’s very hard to tell at this stage, but I think that overcomplicated licences would greatly slow down access to the data and, consequently, delay the development of services to the community and the possibility of creating sustainable business. That’s why my choice goes to a single PDC licence agreement, possibly the Open Government Licence itself, in order to get services quickly developed and available.

Q4 Will the benefits of changing the models from those in use across Government outweigh the impacts of taking out new or replacement licences?

I reckon there will be situations in which changing the models will have a positive impact as well as some cases in which there will be a local negative impact. We need to look at the overall benefit to society.

Oversight

Q1 To what extent is the current regulatory environment appropriate to deliver the vision for a PDC?

I would say the current regulatory environment is appropriate and ready to deliver the vision for a PDC, having already produced a very effective OGL. The problem is not in delivering the PDC, it is rather in questioning the need for the corporation tout-court.

Q2 Are there any additional oversight activities needed to deliver the vision for a PDC and if so what are they?

The only oversight activity needed at this stage is a deep analysis questioning the need for a PDC. I would strongly recommend to question the need for charging and using licences other than the OGL. A PDC charging for data risks to destroy the thriving open data ecosystem and deprive the community of great services. The development of a rich ecosystem will generate, at some point, an income for the Government through taxation. It’s just not the moment to think about directly charging for data.

Q3 What would be an appropriate timescale for reviewing a PDC or its constituent parts public task(s)?

I would recommend an ongoing review to be held no more than every 7-8 months, no less than every 18 months.

This is my response to the Open Data Consultation run by Cabinet office:

“My name is Giuseppe Sollazzo and I work as a Senior Systems Analyst at St. George’s, University of London, dealing with projects both as a consumer and a producer of Open Data. In one previous job, I was dealing with clinical data bases so I would say I developed a certain feeling for issues around the topic of this consultation both from a technical and policy-based perspective.

An enhanced right to data

I believe this is the crucial point of the consultation: the Government and the Open Data community need to work side by side in developing a culture that fosters openness in data. The consultation asks specifically what can be done to ensure that Open Data standards are embedded in new ICT contracts and I think three important points need to be made:

1) independent consultants/advisors need to be taken on board of new ICT projects when the tendering process is started; such consultants need to be recognised leaders of the Open Data community and their presence should ensure the project has enough drive in its Open Data aspects.

2) Open Source solutions need to be favoured over proprietary software. There are Open Source alternatives to virtually any software package. Should not this be available, a project should be initiated to develop such a solution in-house with an Open Source licence. Albeit not always free, Open Source solutions will offer a standard solution for a lower price, and will create possibilities for resource-sharing and business creation.

3) ICT procurement needs to be made easier. Current focus of ICT procurement in the public sector is mostly on the financial stability of the contractor. I argue it should rather be on reliability and effectiveness of the solution proposed. Concentrating the focus on financial stability is a serious mistake, mainly caused by the fact that contractors will develop proprietary solutions; a bankruptcy becomes a terrible risk because of the closedness of the solution; because no other company would be able to take it where the former contractor left; hence the need of strict financial requirements in the tenders. I object to this. In my view, relaxing the financial requirements and moving the focus to the quality of the solution, its openness, its capability to create an ecosystem and be shared, its compatibility with open standards, will improve the overall effectiveness of any ICT solution. Moreover, should the main contractor go bankrupt, someone else will be able to take their place, provided the solution was developed according in the way I envision: consequently, no need for strict financial requirements.

Setting Open Data Standards

As I have already stressed in the previous paragraph, the Government will need to change its rules of access to ICT procurement. Refocusing the attention to openness, standards, ability to re-share the software, is the way to go to start setting a new model in the Open Data area. Web standards can be used and they can represent an example to follow to create new data standards. Community recognised leader can help in this process.

Corporate and personal responsibility

It is absolutely important that common sense rules are established and make into law. The goal of this is not to slow operations down, but to ensure that the right to data mentioned earlier on is actually enforced.

The consultation asks explicitly how to ensure the commitment to Open Data by public sector bodies. I believe that, despite many people feeling that the Government should “stay away”, there is a strong need for smart, effective regulation in this area. Think about the Data Protection and the Freedom of Information Act. Current legislation requires many public bodies to deal with data-sensitive operations, and most do so by having a Data Protection Officer and a Freedom of Information Officer. I believe that an Open Data Officer should operate in conjunctions with these two, and that this would not require many more resources than already allocated. The Open Data Officer should drive the publication of data, and inspire the institution they work for to embrace the Open Data culture.

The Government should devolve its regulatory powers in this area to an independent authority to be established to deal with such regulatory issues. I envision the creation of Ofdata on the model of Ofcom for communication and Ofsted for education.

Meaningful Open Data

A lot of discussions have been going on about the issue of data quality. Surely, the whole community aims for data to be informative, high-quality, meaningful and complete. Unfortunately, especially at the beginning of the process, this is hard to reach.

I think that lack of quality should never be a reason for publication to be withheld: where data is available, it should be published. However, I also believe that quality is important and that is why the Government should publish datasets in conjunction with a statistical analysis and independent review (maybe run by the authority I introduced in the previous paragraph) that assesses the quality of the dataset. This should serve two goals: firstly, it would allow open data consumers to deal with error and interpretation of data; secondly, it would help the open data producer to investigate problems in the process leading to the publication and setting goals in its open data strategy.

The final outcome of this publish-and-assess procedure would be a refined publication process that informs the consumers and the public about what to expect. Setting a frequency of update should be part of this process. Polishing the data should not: data should always be made available as it is, and if deemed low quality it should be improved at the next iteration.

There are questions about how to prioritise the publication of data. I believe that in this respect, and without missing the requirements of the FoIA, the only prioritisation strategy should be requests numbers: the more a dataset the public requests, the higher priority it should be given in being published, improved, updated.

Government sets the example

I think the Government is doing already a good job with this Open Data consultations, and I hope it will be able to take the lessons learnt and develop legislation accordingly.

Unfortunately, in many areas of the public sector there is still a “no-culture” responsible for data not to be released, Freedom of Information requests going unanswered, and general hostility towards transparency. I have heard a FoI officer commenting “this is stuff for nerds, we don’t need to satisfy this kind of need” to Open Data requests. This is a terrible cultural problem preventing a lot of good to be done.

I believe that the Government should set the example by reviewing and refining its internal procedures for the release of data and responding to FoI requests in a more simple, compassionate way, stressing collaboration with the requestor rather than antagonism.

Moreover, it should be the Government’s mission to organise workshops and meetings with Open Data stakeholders in the public sector, to try and create a deeper perception of the issues around Open Data and its benefits. Being on http://data.gov.uk should be standard for any public sector institution, and represent an assessment of their engagement with the public.

Innovation with Open Data

The Government can stimulate innovation in the use of Open Data in some very simple way. Surely it can speed up awards and access to funding to individuals and enterprises willing to build applications, services, and businesses around Open Data. This should apply to both for-profit and not-for-profit ventures, and have as only discriminating factor the received social benefit to their communities or to the wider public.

The most important action the Government can take to stimulate innovation is, however, simplification of bureaucracy. Making Company Law requirements easier to satisfy, as we have already discussed for ICT procurement, is vital to bring ideas to life quickly. Limiting legal liability for non-profit ventures is also a big step ahead. Funding and organising “hackathons”, barcamps, unconferences, and any other kind of sponsored moment where developers, policy makers, charities, volunteers can work together, is also a very interesting way of pushing innovation and making it happen.

Open data offers an amazing opportunity of creating “improvement-by-knowledge”. Informed choice, real time analysis, accurate facts, can all be part of a new way of intending democracy and innovation, and the UK can lead the way if its leaders will be able to understand the community and provide it with the appropriate rules that make its tools work and the results happen. This way, we will have a situation where services can be discussed and improved, and public bodies can have a chance to adjust their strategy; where citizens can develop their ideas, change the way they vote, take their leaders to account; and, as a result, communities can work together, and society can be improved.“

Not everyday you get the opportunity to attend an event at Cabinet Office. Moreover, not everyday they’re inviting you to an event you actually care about. Hence, here I am at 22 Whitehall for a discussion about the Open Data Consultation with their Transparency Team.

The people attending this kind of events usually belong to the following tribes:

- developers want data to be released as quick as possible and have in mind possible applications/visualisations/uses of the data; tend not to care much about the legal implications

- openness campaigners push for data to be released no matter whether they can be useful or not; their only concern is transparency (“you’ve got nothing to hide, right?”)

- privacy campaigners are not necessarily against data release, but are over-worried about big-brotheresque implications (where Big Brother is in this case your car insurer, rather than the Government)

- policymakers which is a cool description of the average Civil Servant involved in this: they support data to be released with moderation, and are usually worried. And they don’t know about what.

Such a diverse gathering incurs easily in the risk of over-generalising the discussion, which is technically what has happened. However, I guess this was exactly the goal of the Cabinet Office Transparency Team: see how these different people tend to perceive the Open Data issue, and what common grounds can be found. Necessarily, such common grounds are generalistic and tend to involve a discussion about fears, hopes, effects of data releases, and what they want from each other.

The workshops was pretty much interactive and helped each person interact with others and get in contact with, sometimes, a completely different point of view. Evidently there are many hopes about Open Data: that it can be better, quicker, machine readable, and most importantly linked. Many people attending the workshop also stressed they would like the process of data release to be more transparent. Also some fears were made explicit, especially about the possibility of low-quality, meaningless, data being released.

I think, however, that the two most important points made in this respect were

- sustainability of the data infrastructure: we don’t want Open Data to be released and go offline the day after because the server is engulfed by excessive demand; sustainability also in the sense that we want the agency releasing the data defining a process for updating the data.

- engagement: the agency releasing Open Data needs to set up a way to interact with developers and campaigners to respond to their queries about the data released, and possibly some kind of “customer service” structure.

I strongly believe these two points to be the key to make the Open Data movement successful and I was frankly surprised of hearing someone dismissing them as “we just want the data”. Although I agree that some data is better than no data, we shouldn’t be driving the system to the frustrating situation in which we can’t affect the Open Data release process because such process hasn’t been defined properly. Moreover, although sometimes low-quality data is acceptable if there’s no alternative, I wouldn’t push the agencies to release data whose quality hasn’t been assessed: we don’t want to drive the whole quality down.

I fully understand that in the view of the Government and of some campaigners Open Data release can be a way to deal with Freedom Of Information requests in a more automatic way, and this surely means that data must be released as and when available. However, we have a historical chance to define the way data should be made public and what kind of added value we expect from them. This is an opportunity not to be missed.

Some interesting points were made when discussing what to expect from the Government and from the other actors. For example, the idea of re-sharing seems to be finally part of the common culture of data: most users are ready to be both users and consumers of open data, and push for everyone to make their data available. These data can be, in turn, derivative data from the original agency: a process that can enrich and empower the final users.

I do not particularly agree with those saying that Government should set the data release and step out of the game: I think that there is a need for a central assessment of the quality of data in order to avoid “crap data” to become mainstream and I can’t see many alternatives to a central agency, as Ofcom is for communications or Ofsted for education. What the Government needs to do is to make such procedures simple, to help other actors to release Open Data with an easy legislation, and to extend access to procurement for SMEs who currently struggle to satisfy the financial requirements even though they might offer better services than bigger companies. I believe that the Government should maintain its regulatory powers in this context in order to make data more relevant, accessible, democratic, genuinely open.

There is some concern about privacy, of course. One of the main point is that once you start releasing data you don’t know how these will be used and by who. Worringly, data don’t need to be directly referring to a person to identify them. Identification is not a binary function. The classical example is how a car insurance company (yes, I pick on them easily!) can alter its prices after analysing crime rates data. This is something they couldn’t do before. In a way, where I live now identifies me strongly than before, and the car insurer can amend their behaviour towards me because of Open Data although they don’t have perfectly identifiable information about me.

Should this prevent crime data to be released? I don’t think so. I would rather call for more regulations and for punishing this kind of behaviour, but I also think this concern shouldn’t be part of the Open Data movement: we only need to care about transparency and, in my case, efficiency of the systems that will be used to release the data. Concerns about privacy need to be addressed, but abuse of data is a widespread problem that does not affect only the Open Data context, so it should be tackled by another, more general, task-force.

I will be commenting about the points of the Open Data Consultation in a following post. For the time being, I would recommend reading what Chris Taggart has written about his response to the ODC.

[Disclaimer: this post represents my own view and not that of my employer. As if you didn’t know that already.]

Do the words “mobile portal” appeal to you?

I have been working extensively, with a small team, to launch St. George’s University of London‘s mobile portal since last January after we decided to go down the road of a web portal rather than that of a mobile app. The reason for this choice is pretty clear: despite the big, and growing, success of mobile apps, we didn’t want to be locked in to a given platform or to waste resources on developing for more platform. Being a small institution it’s very difficult to get resources to develop on one platform, even less on multiple ones. We also wanted to reach more and more users, and a mobile portal based on open, accessible, resources made perfect sense.

As many of the London-based academic institutions, St. George’s needs to account for two different driving forces: the first is that as an internationally renowned institution it needs to approach students and researchers all over the world; the second is that being based in a popular borough it is part of the local community for which it needs to become a reference point, especially in times of crisis. Being a medical school, based in a hospital and a quality NHS health care structure, emphasizes a lot the local appeal of this institution.

This idea of St. George’s as an important local institution was one of the main drives behind our mobile portal development. We surely wanted to provide a good, alternative, service to our staff and students, by letting them access IT services when on the move. However, the idea of reaching out to people living and working around us, to get St George’s better known and integrated within its own local community, lead us to a thriving experience developing and deploying this portal. “Can we provide the people living in Tooting, Wandsworth, and even London, with communication tools to meet their needs, while developing them for people within our institution?” we asked ourselves. “Can we help people find more about their local community, give them ideas for places to go, or show them how to access local services?“.

This coalition government had among its flagship policy that of a “Big Society”, having the aim “to create a climate that empowers local people and communities”. Surely a controversial topic, nonetheless helpful to rediscover a local role for institutions like us to get them back in touch with their own local community, which in some case they had completely forgotten.

In any London borough there are hospitals, universities, schools, societies, authorities. No matter their political affiliation, if each of these could do something, they would improve massively the lives of the people living within their boundaries. Can IT be part of this idea? I think so. I believe that communication in this century can and does improve quality of life. If I can now just load my mobile portal and check for train and tube times, that will help me get home earlier and spend more time with my family. If I can look up the local shops, it will make my choices more informed. It might get me to know more local opportunities, and ultimately to get me in touch with people.

Developing this kind of service doesn’t come with no effort. It required work and technical resources. We thought that if we could do this within the boundaries of something useful to our internal users, that effort would be justified, especially if we tried to contain the costs. With this view in mind, we looked for free, open-source, solutions that we might deploy. Among many frameworks, we came across Mollyproject, a framework for the rapid development of information and service portals targeted at mobile internet devices, originally developed at Oxford University for their own mobile portal. When we tried it for the first time, it was still very unstable and could not run properly on our servers. But we found a developers community with very similar goals to ours, willing to serve their town and their institution. We decided to contribute to the development of the project. We provided documentation on how to run the Molly framework on different systems, and became contributors of code. Molly was released with its version 1 and shortly afterwards we went live.

Inter-academic collaboration has been a driving force of this project: originally developed for one single institution, with its peculiar structure and territorial diffusion, it was improved and adapted to serve different communities. The great developments in the London Open Data Store allowed us to add live transport data to the portal, letting us have enthusiastic reactions from our students, and these were soon integrated in the Molly project framework with great help from the project community. I think this is a good example of how institutions should collaborate to get services running. A joint effort can lead to a quality product, as I believe the Molly project is.

The local community is starting to use and appreciate the portal, with some great feedback received an the Wandsworth Guardian reporting about a “site launched to serve the community”. I’m personally very happy to be leading this project as it is confirming my idea that the collaborative and transparent cultures of open source and open data can lead to improved services and better relationships with people around us, all things that will benefit the institutions we work for. The work is not complete and we are trying to extend the range of services we offer to both St. George’s and external users; but what we really care and are happy about is that we’re setting an example to other institution of how localism and a mission to provide better services can meet to help build better communities.

Open Data and User Experience

Can Open Data be an opportunity for better services, with respect with user experience? Certainly so.

As noted on the Public Strategist blog, the current Bus Countdown display is not the best ever: it gives information too far in the future in a way that isn’t suited to someone already at the bus stop, unless they’re polling the display for information going back and forth from their home.

Pretty obviously, when there is just one single means through which this kind of information are spread to the public, usability is managed centrally by the authority in charge of such information. Surely, this authority might invest on usability and accessibility and let people access such information in multiple formats on different devices or by different means.

As Public Strategist suggests, if I’m at the bus stop I’ll just need to know when the next bus will come; say I’m waiting for bus number 91: I’m not interested in knowing I have three 91 buses coming in half an hour, I just need the first, maybe the second. However, when I’m at home I might want to know when all the next “instances” of a given bus will pass in a longer term.

This is exactly where the open data revolution can make a difference: by letting developers play with the data, they can propose novel solutions to the public, better interaction models, or simply a number of different ways to access the information – number that a single, resource-constrained, organisation is unable to manage.

Open Data are a liberating tool for Government transparence; but they can also empower designers and developers to create a better experience for the public. This is surely a very important, although less ideological, reason why local authorities and larger organisation should welcome this revolution.

Launching a mobile app

I know. I’ve been silent for too long.

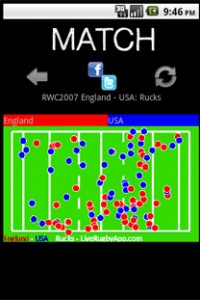

The reason is, as most of you know already, I’ve been developing and launching a mobile app. LiveRugby, inspired by the awesome work made by Colm on his TotalFootball and StatsZone apps, promises to be the definitive way to generate and share graphical analysis and statistics for the data-centric rugby fan during the next World Cup. I chose an app about rugby because is something I understand and I’m passionate about. I wanted to learn more about rugby, and more about mobile applications, and this seemed the best opportunity.

I still can’t say much as many information are, in a way, “secret” until and I need to get some clearance from one of the suppliers. But, I promise, I’ll be writing soon about it.

For the moment, let me just give you a list of what I wanted to experiment with this venture:

- Planning the application

- Dealing with the supplier of data, OptaSports

- Being able to project manage myself

- Research what kind of statistics might be useful in a sport like rugby and how to display them in a way that is easy to understand to the average fan

- Develop a full application on my own

- Being able to outsource part of the artwork to a graphic designer

- Launch the app on the market

- Start a marketing campaign on my own getting in touch with press and media

- Communicating and satisfying customers-users

At the moment the app is launched on the Android market, although I’m already working for an iPhone version for the RBS 6 Nations. Of course, a business venture like this is successful when a profit is made out of it.

However, there are several other measures of success that I need to take in account, roughly at every point of this list.

Whether this project has been a success or not will be subject to analysis and to a more detailed blog post when it will be time to make a balance. For the moment, I’m totally enjoying the learning experience it has been so far, and the constant challenge posed by launching your own enterprise.

I’d like to know what my readers think 🙂

A couple of weeks ago my flatmate, Claudio, was called by a very angry Police officer who wanted to question him as a possible suspect for breaking some other guy’s ribs at Leicester Square tube station on a night last December. Everyone who knows him would consider this very possibility almost a funny one to think about. However, the whole episode was great to think about… privacy and data!

The first thing that comes to the mind of the person being questioned, and being confident of their own innocence, is “I need an alibi“. “It was not me” is not sufficient to the Police, they will ask “Ok – so what where you doing that day at that time“?.

Of course, when asked this question you are surprised enough, and possibly shocked and worried about consequences, that you don’t necessarily remember. It’s easy to fall into despair. “What will I say?“, he asked me.

This is when I thought about the magic word: “data“.

Each one of us disseminates data about themselves, especially heavy Internet users as we both are. So, the first thing I did was to check my Gmail account. E-mails and chats for that specific date. A day like any other became suddenly meaningful and full of memories.

For example, there was a significant lower amount of e-mails than my average day, a sign that I was mostly out, not at work. It turned out it was a Saturday. It seemed from my e-mails that I was heading to a party that night: it turns out I was at my rugby team’s Christmas party.

Why is what *I* was doing useful to Claudio? Very simply, because we spend most Saturday evenings with the same group of friends. Apparently I was not with him that Saturday – I could not be his alibi. It also seemed I checked back at my station around 11pm. A very early time to go back home on a Saturday after a party. What happened?

Before despairing, I made a step back to the e-mail flow and found a very peculiar e-mail at about 1230 saying just “Klaus” and a phone number. Funnily enough, I don’t know anyone called Klaus so… who is Klaus? Why did I mail his number?

You should know that I live between Alexandra Palace and Wood Green and I have this habit of walking to Muswell Hill for a coffee on Saturday mornings. I also tend to have lunch at home. So, 1230… I was probably on the way back from Muswell Hill. So I started – using OpenStreetMaps – to check for all possible locations I tend to visit on the way back. There’s a shop, a tennis club I’ve played at, a friend who lives at the corner of the tennis club, a couple of cafes, and a Piano shop.

That’s when the Eureka bulb switched on.

I headed to Facebook: not many status updates, but one very important with a photograph. A single photograph showing me in a bus, on the way back home, with heavy snow outside!

I remembered that to avoid the snow I entered the Piano shop. I was moving to another flat at the time, and was investigating the possibility of getting a free piano from the Freecycle. I entered the piano shop to enquire about the cost of piano removals – Klaus being the name of the van man. That’s also why I headed back home very early after the party: I was worried about transport not working because of the snow. I remembered I found Claudio at home when I was back.

I checked again my e-mails and chats: the flow interrupted around 6pm. Basically, there was a hole of about 4 hours in which I didn’t know where Claudio was. Still, we had a track of where and when to look at. There was no chat/e-mail/facebook status update from him on that night, suggesting he had been out, too. Hence, we contacted all our common friends he could have been with that night. All of a sudden he said: “Now I remember it all! After you went out, I called Jasmin and went with her for dinner at Satsuma with her friend visiting from america“. In less than 20 minutes, photos showing him in the restaurant were in his e-mail account.

More interestingly, it turned out he actually was at Leicester Square tube station when the police claims he was. More worringly, he had been alone for some time before meeting his friend.

I’m not a good thriller writer. The finale is probably obvious to you now. He had touched his Oyster card out at the same time the person the Police is looking for was in the view of a CCTV camera. Of course when Police showed us the pictures, it was obviously not him: they had called him because his Oyster card is registered.

But can you see why I’m amazed by this story? A day of which we couldn’t remember anything is now a story full of details.

Moreover: there was an accusation built on data (coming from the Oyster Card system), to which we found a defense built on data (coming from Gmail, Foursquare, and Facebook).

I began to think what this story would have been before Gmail, before Facebook, before check-ins? I know the answer: Claudio would have gone to the police scared, unable to answer the questions in all of his honesty, almost sure he had no way of defending himself. Instead, thanks to this data society he was able to go there without any fear, ready to hear their story and to respond to their questions, being sure he knew every move of that day.

Online services have become our memory.

Don’t get me wrong: I still find problematic the use of users data and the way most online companies deal with privacy. It’s maybe scary the fact that on-line strangers-managed services have become a replacement for our own memory. However, the mountain of data they allow us to have access to can be useful and helpful. The question is how to make good use of these data, and store them in a secure and private way that allow us to decide who we want to share the data with (luckily not the Police).

Personal lesson learnt: I will now save all my Oyster history (before it expires every 3 months), check-ins, and latitude. I want to be ready for questioning.